While watching Horse-Being (Être Cheval), which is a lot about embodiment, I developed a bad case of motion sickness. It started as dizziness—I had to pause the film a few times—and then when the film ended, it became full-body nausea. I laid down and closed my eyes and took some deep breaths but my brain was spinning. I told myself “It’s OK, you’re grounded,” and imagined my spine resting on the bed, but then my spine started spinning out of control too.

I’m very sensitive to motion so this is not a slight against the film. In Horse-Being, the motion sickness came from the handheld camera, specifically the shots that follow the motion of Karen Chessman, the protagonist, as she is being trained to be a pony. Her movement as a pony is jerky and halting. She wears boots that resemble horse hooves, which are very high heels without the heel, and has to walk over a dirt field, and then later pulls her trainer, Foxy Davis, in a cart over the same field. In these scenes I saw how much hard work it is to be a pony. Karen pants and sweats in a PVC catsuit, she yanks at the cart, she has to stop from exhaustion. The camera jolts and pulls too.

Karen is an artist, performer, and poet who has come to Florida from France to be trained on Foxy’s rural property in the BDSM practice of pony-play. Karen’s artistic work is never mentioned in the film, which begins with and ends at what seems to be a few days of training. Foxy, with his handlebar moustache and jean outfits, embodies a cowboy in the same way that Karen embodies a pony. There’s a scene where Foxy taxidermies a bird and the camera observes a plastic shape that the bird’s feathery exterior is being wrapped around, the new plastic innards of the bird that will replace its living organs. The image reminds me of how in the liberal economy, individuals are cast as minds that puppet their bodies, a model that flesh rests upon. The model moves their flesh through the world, enacting their will first on their flesh and then the world. (I tried to command my body to not be sick and failed.)

At one point in the film, Karen says that horses are a symbol of freedom. The filmmaker Jérôme Clément-Wilz interjects, “But you’re not exactly free yourself… in the corral.” Karen replies, “No that’s just the training, it’s consensual… Not like in society… This life of submission, obedience, etc. It’s unbelievable. The real S/M is the everyday life of people. Suffering, obeying to assholes, to bosses. To not have money, and have to beg… It is not what we are doing here.”

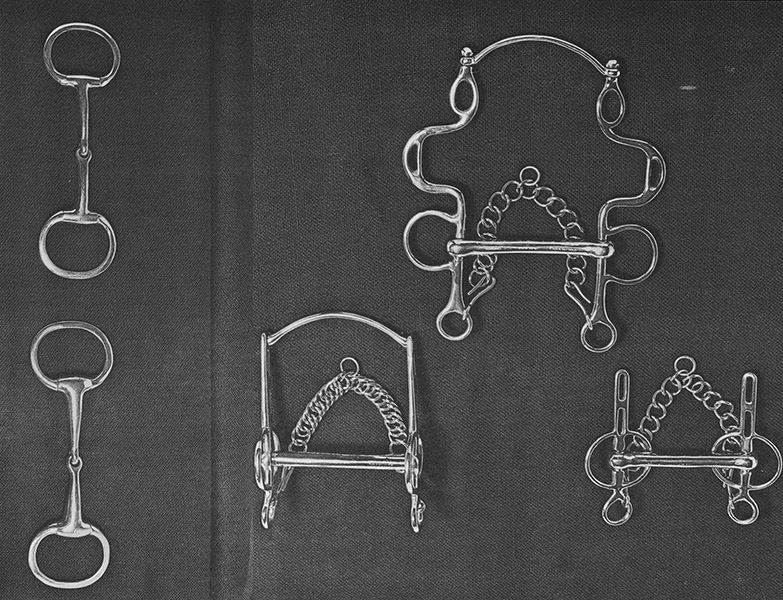

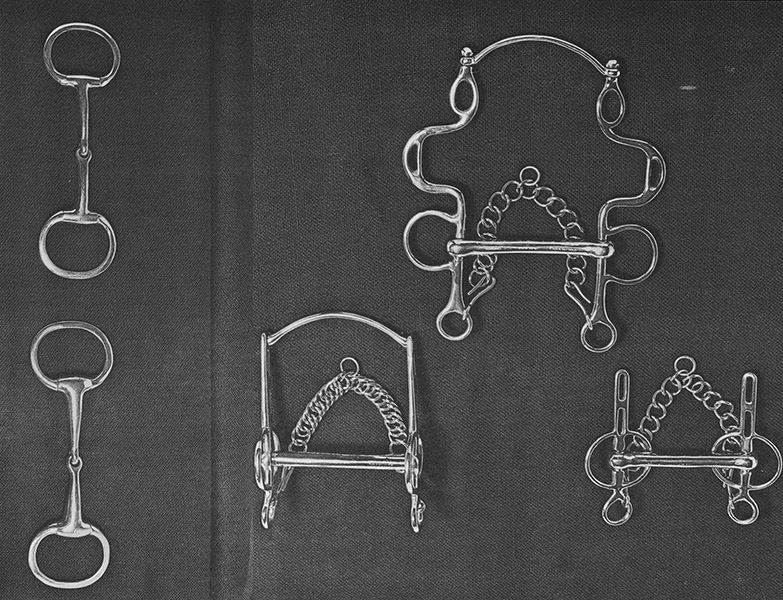

I see her bliss while strapped in the bridle, blindfolded, drooling over the bit in her mouth. There’s no literal sex between her and Foxy but it’s clear how sexy it is to be in the paradoxical state of submitting-not-submitting, of having no control while being in total control. Foxy talks about how the goal of training in pony-play is achieving a kind of “mental telepathy” between pony and rider. He says that he looks for “complete submission,” he “doesn’t speak commands.” The relationship makes both pony and owner/rider completely alert in body. The erotic means being alive in all the senses, only in the present, cut off from the demands of the future and past. It’s a kind of extreme safety.

The film makes a parallel between Karen’s gender (as she says, she’s “not trans or anything, I’m just nowhere… I’m a punk”) and her training to be a pony. Early on, there’s a scene of her shaving and talking about gender, and later, several others of her putting on make-up or the corsets of the pony outfit. But it feels simplistic to read both her gender and pony-play through the lens of liberal self-identification or the freedom to be as one wishes. Both practices comprise more than individual agency. And the horse-horses that run through the film are domesticated. They are majestically dependent. They try really hard to live with, and be taken care of by, their keepers.

Amy Ching-Yan Lam is an artist and writer. She has exhibited conceptual, film, and performance works internationally, both solo and as part of the collective Life of a Craphead. Her poetry chapbook titled The Four Onions was published by yolkless press (2021) and a full-length collection is forthcoming with Brick Books in 2023. Her first job was serving BBQ beef on a bun at the Calgary Stampede.

While watching Horse-Being (Être Cheval), which is a lot about embodiment, I developed a bad case of motion sickness. It started as dizziness—I had to pause the film a few times—and then when the film ended, it became full-body nausea. I laid down and closed my eyes and took some deep breaths but my brain was spinning. I told myself “It’s OK, you’re grounded,” and imagined my spine resting on the bed, but then my spine started spinning out of control too.

I’m very sensitive to motion so this is not a slight against the film. In Horse-Being, the motion sickness came from the handheld camera, specifically the shots that follow the motion of Karen Chessman, the protagonist, as she is being trained to be a pony. Her movement as a pony is jerky and halting. She wears boots that resemble horse hooves, which are very high heels without the heel, and has to walk over a dirt field, and then later pulls her trainer, Foxy Davis, in a cart over the same field. In these scenes I saw how much hard work it is to be a pony. Karen pants and sweats in a PVC catsuit, she yanks at the cart, she has to stop from exhaustion. The camera jolts and pulls too.

Karen is an artist, performer, and poet who has come to Florida from France to be trained on Foxy’s rural property in the BDSM practice of pony-play. Karen’s artistic work is never mentioned in the film, which begins with and ends at what seems to be a few days of training. Foxy, with his handlebar moustache and jean outfits, embodies a cowboy in the same way that Karen embodies a pony. There’s a scene where Foxy taxidermies a bird and the camera observes a plastic shape

that the bird’s feathery exterior is being wrapped around, the new plastic innards of the bird that will replace its living organs. The image reminds me of how in the liberal economy, individuals are cast as minds that puppet their bodies, a model that flesh rests upon. The model moves their flesh through the world, enacting their will first on their flesh and then the world. (I tried to command my body to not be sick and failed.)

At one point in the film, Karen says that horses are a symbol of freedom. The filmmaker Jérôme Clément-Wilz interjects, “But you’re not exactly free yourself… in the corral.” Karen replies, “No that’s just the training, it’s consensual… Not like in society… This life of submission, obedience, etc. It’s unbelievable. The real S/M is the everyday life of people. Suffering, obeying to assholes, to bosses. To not have money, and have to beg… It is not what we are doing here.”

I see her bliss while strapped in the bridle, blindfolded, drooling over the bit in her mouth. There’s no literal sex between her and Foxy but it’s clear how sexy it is to be in the paradoxical state of submitting-not-submitting, of having no control while being in total control. Foxy talks about how the goal of training in pony-play is achieving a kind of “mental telepathy” between pony and rider. He says that he looks for “complete submission,” he “doesn’t speak commands.” The relationship makes both pony and owner/rider completely alert in body. The erotic means being alive in all the senses, only in the present, cut off from the demands of the future and past. It’s a kind of extreme safety.

The film makes a parallel between Karen’s gender (as she says, she’s “not trans or anything, I’m just nowhere… I’m a punk”) and her training to be a pony. Early on, there’s a scene of her shaving and talking about gender, and later, several others of her putting on make-up or the corsets of the pony outfit. But it feels simplistic to read both her gender and pony-play through the lens of liberal self-identification or the freedom to be as one wishes. Both practices comprise more than individual agency. And the horse-horses that run through the film are domesticated. They are majestically dependent. They try really hard to live with, and be taken care of by, their keepers.

Amy Ching-Yan Lam is an artist and writer. She has exhibited conceptual, film, and performance works internationally, both solo and as part of the collective Life of a Craphead. Her poetry chapbook titled The Four Onions was published by yolkless press (2021) and a full-length collection is forthcoming with Brick Books in 2023. Her first job was serving BBQ beef on a bun at the Calgary Stampede.