I have never ridden a horse in real life but I've ridden many in video games. I spent hours trotting robotically across the snowy landscapes of Skyrim on a basic brown mare, and galloped through New Mexico's deserts on a snow white Arabian in Red Dead Redemption 2. I leapt off the cliffs of Greek islands atop a unicorn named Phobus who trailed rainbow glitter from her hind quarters in Assassin's Creed Odyssey, then chased after wild ponies with pink and blue spots in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Covering ground on horseback is essential to the frontier myths driving the action and geography of these role-playing games (RPGs): the adventure involves uncovering a foggy map whose details fill in as the player roams previously unexplored space. Chickasaw theorist and video game scholar Jodi Byrd argues that a colonial, Manifest Destiny myth structures the spatial imaginaries of video games, and that playing otherwise would involve radically reimagining the geographies and stories driving such games.1 Thinking with Byrd's provocation, I wonder what it would feel like to brush, feed, and pat my horse long past refilling her stamina meter for the next mission. I could dismount in some pastoral meadow, sit down under a tree, and watch her graze, without a care in the world for story progress.

Many horse-riding RPGs include a mini game where the player captures and tames a wild horse, and often, this is how you find the "best" horses in a game: the ones that can't be bought from stables. This is the gamification of those tense, charged moments from movies about horse trainers: Robert Redford in the Horse Whisperer (1998) or Brady Jandreau in The Rider (2017). The mini game is an apt encapsulation of everything that is wonderful about wildness, and a depressing confrontation with the drive humans have to contain and possess it. I stalk the animal, slowly approaching without making any sudden movements. In Red Dead Redemption 2, the controller vibrates according to the wild horse's heart beat: if it's vibrating quickly, I know the horse is scared, and as it slows, I'm assured the horse is calming down and I can inch a bit closer. By pressing the triangle button at just the right time, I can calm the horse: "easy girl," my character says in a chesty, Southern baritone. Once I'm close enough, I move to mount up and a bit materializes in the horse's mouth. In Zelda, this is the moment where the game suggests I "press L to soothe" the terrified horse, so I punch that button frantically. I have to fight to stay on, keeping my balance with the controller until the horse tires out. When the bucking stops, the wild horse is tamed: being becomes property.

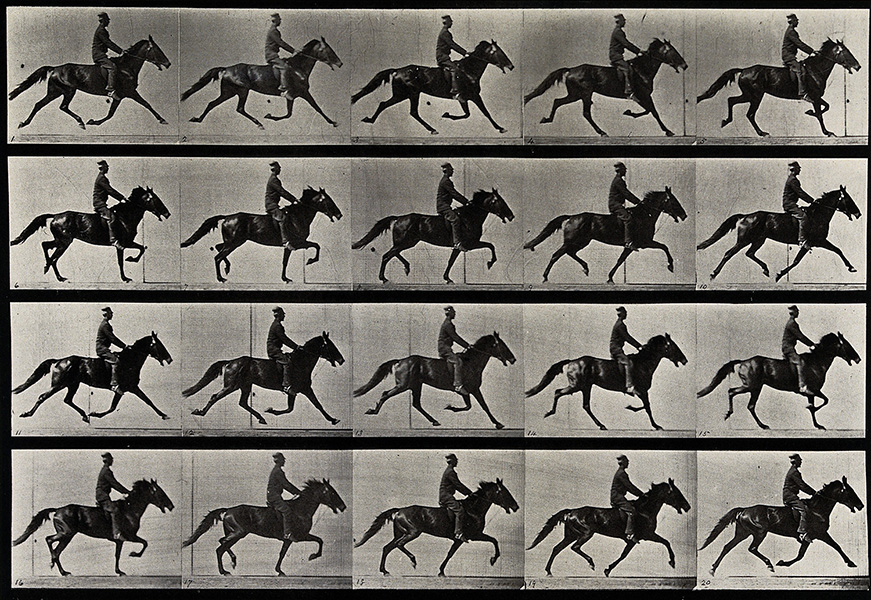

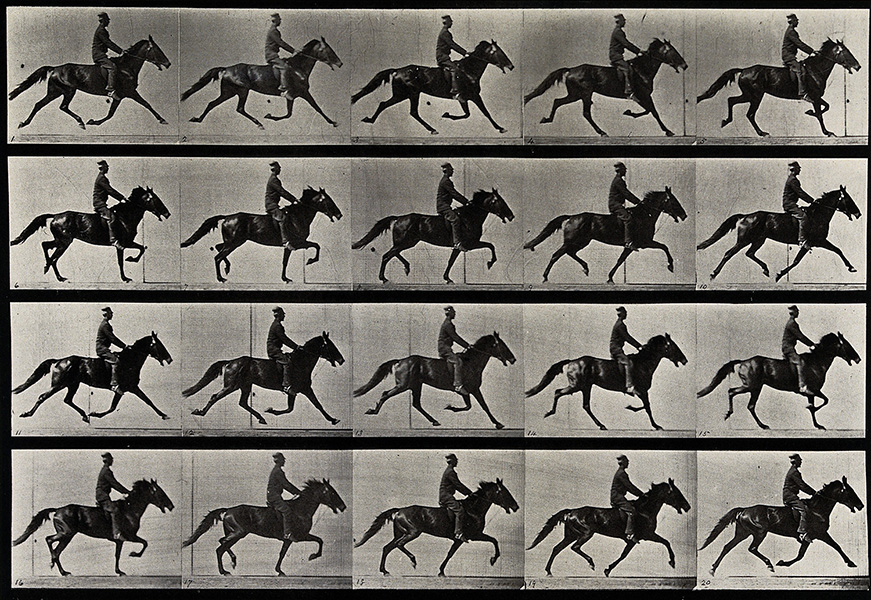

The appeal of these horse-breaking mini games lies in game physics, which describes motion, gravity, and rules for how objects and bodies react with space and each other in a particular game world. Game physics for realistic scenarios, like riding a horse, are developed partly through the use of 3D motion capture data: real horses and riders are recorded wearing motion capture suits and their movements are used to generate objects with consequences in a game world. The queer video games scholar Bo Ruberg argues that game physics reflect the worlds that their developers and anticipated players have the capacity to imagine.2 For example, the gigantic, bouncing boobs and butts on femme characters like Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider franchise move in the ways that they do because their physics develops out of misogynist frameworks. Ruberg is interested in imagining how a queer game physics divorced from normative understandings of motion and bodies would look, feel, and play out. A horse who never stops bucking, or can't be mounted, or even one who doesn't bother to put up any fight would wreck the taming challenge in a queer sort of way.

Motion capture data is hard to produce for large animals and game studios tend to buy this data from third-party libraries. Cetroid3D, a motion capture outfit based in the U.K., documented its process of creating an equine motion capture library, scanned on location at the Sparsholt Equine Centre in Hampshire. In the video the handler and horse are both wearing motion capture suits in an indoor practice ring with a soft, dirt floor.3 They perform many different maneuvers that might be useful in video games: rearing up, turning quickly to the left and right, trotting around. There is one maneuver shared by horse and rider whose utility to most games is less clear: the rider gently helping the horse to lay down.

The rider bends the horse's front left leg backwards at the knee, pulling the hoof sharply upwards towards the body by a tether. Simultaneously, she pulls the reins down toward the ground on the animal's left side. The horse drops to her left knee, while the handler continues to pull the horse's head sideways and downwards. The horse is resisting, not because she is afraid but because, for a horse, being forced to lie down is an unnatural maneuver toward vulnerability. Horses do choose to lie down in their day-to-day lives, to cool off or sleep, but they want to be in control of when, how, and where this happens. This motion capture horse is well trained, she quits resisting and folds onto her left side, laying her head down in the practice ring dirt. The rider lays her hand firmly on the horse's shoulder, says something inaudible, perhaps in comfort, then walks away backwards, drawing her hand and then finger along the horse's flank as she retreats outside the frame, as if to say "stay down, you're okay." After a few moments, the handler returns and pats the horse on the shoulder, telling her with this gesture that she can get back up, then the handler jumps out of frame again.

It takes a great deal of training to get a horse to lie down on command, and the technique is controversial: some "horse whisperers" who specialize in taming the orneriest of mustangs, argue that this maneuver, when done safely, reduces aggression, because it forces the horse to embody a submissive pose. Others argue that forcing a horse to lie down is manipulative, dangerous, and that forced submission is not a generative way of being in relation with animals. I don't know anything about horses so I can't weigh in, but I do know that in the thousands of hours I have spent riding horses in video games, I have never seen one lay down. I have only seen them die.

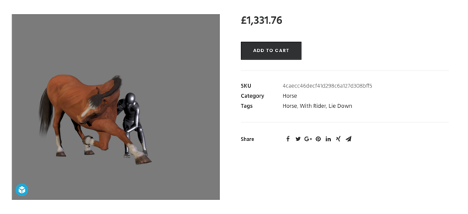

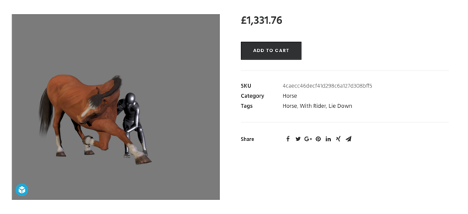

It takes a great deal of training to get a horse to lie down on command, and the technique is controversial: some "horse whisperers" who specialize in taming the orneriest of mustangs, argue that this maneuver, when done safely, reduces aggression, because it forces the horse to embody a submissive pose. Others argue that forcing a horse to lie down is manipulative, dangerous, and At £1,300, this lie-down gesture is by far the most expensive horse motion capture data in Centroid’s library (most gestures cost £200). Lying down is the closest approximation of playing dead that a real horse will perform for a camera, and horses need to die a lot in video games. The horse's work to rise back to her feet in the second half of the clip is useful for scenes in which a fall from heights, or an arrow to the side, is enough to knock a horse down, but not to kill her. The tender, slow exchange between horse and rider as the animal is eased gently towards the ground in the motion capture could not be farther apart from the violence of killing horses in video games.

When the human figure guiding the horse to the ground is excised from the motion capture data, the horse simply crumples to the ground and dies. But the trust, and whispered words between horse and rider are still in there somewhere, shadows in the data that drives the action at some deeper level. These are traces of care to ponder in that meadow, wasting time watching my living game horse graze.

1 Jodi Byrd, “Indigenomicon,” Talk for SFU Digital Democracies Institute, 5 May 2021. Summarized here by Amy Harris: https://digitaldemocracies.org/jodi-byrd-indigenomicon/.

2 Bo Ruberg, “Queer Physics: The Gendered and Sexual Implications of How Video Games Move,” Talk at Society for Cinema and Media Studies Conference, 17 March 2021. Summarized here: https://twitter.com/SCMSQT/.

3

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbNeRjfEPkw, see minute 2:10.

Cait McKinney is Assistant Professor in the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University. They are the author of Information Activism: A Queer History of Lesbian Media Technologies (Duke University Press, 2020), winner of the Gertrude Robinson Best Book Prize from the Canadian Communication Association, and a Lambda Literary Award Finalist for LGBTQ studies. They co-edited (with Allyson Mitchell) Inside Killjoy’s Kastle: Dykey Ghosts, Feminist Monsters, and Other Lesbian Hauntings (UBC Press and Art Gallery of York University, 2019), and a 2020 special issue of First Monday on HIV/AIDS and Digital Media.

I have never ridden a horse in real life but I've ridden many in video games. I spent hours trotting robotically across the snowy landscapes of Skyrim on a basic brown mare, and galloped through New Mexico's deserts on a snow white Arabian in Red Dead Redemption 2. I leapt off the cliffs of Greek islands atop a unicorn named Phobus who trailed rainbow glitter from her hind quarters in Assassin's Creed Odyssey, then chased after wild ponies with pink and blue spots in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Covering ground on horseback is essential to the frontier myths driving the action and geography of these role-playing games (RPGs): the adventure involves uncovering a foggy map whose details fill in as the player roams previously unexplored space. Chickasaw theorist and video game scholar Jodi Byrd argues that a colonial, Manifest Destiny myth structures the spatial imaginaries of video games, and that playing otherwise would involve radically reimagining the geographies and stories driving such games.1 Thinking with Byrd's provocation, I wonder what it would feel like to brush, feed, and pat my horse long past refilling her stamina meter for the next mission. I could dismount in some pastoral meadow, sit down under a tree, and watch her graze, without a care in the world for story progress.

Many horse-riding RPGs include a mini game where the player captures and tames a wild horse, and often, this is how you find the "best" horses in a game: the ones that can't be bought from stables. This is the gamification of those tense, charged moments from movies about horse trainers: Robert Redford in the Horse Whisperer (1998) or Brady Jandreau in The Rider (2017). The mini game is an apt encapsulation of everything that is wonderful about wildness, and a

depressing confrontation with the drive humans have to contain and possess it. I stalk the animal, slowly approaching without making any sudden movements. In Red Dead Redemption 2, the controller vibrates according to the wild horse's heart beat: if it's vibrating quickly, I know the horse is scared, and as it slows, I'm assured the horse is calming down and I can inch a bit closer. By pressing the triangle button at just the right time, I can calm the horse: "easy girl," my character says in a chesty, Southern baritone. Once I'm close enough, I move to mount up and a bit materializes in the horse's mouth. In Zelda, this is the moment where the game suggests I "press L to soothe" the terrified horse, so I punch that button frantically. I have to fight to stay on, keeping my balance with the controller until the horse tires out. When the bucking stops, the wild horse is tamed: being becomes property.

The appeal of these horse-breaking mini games lies in game physics, which describes motion, gravity, and rules for how objects and bodies react with space and each other in a particular game world. Game physics for realistic scenarios, like riding a horse, are developed partly through the use of 3D motion capture data: real horses and riders are recorded wearing motion capture suits and their movements are used to generate objects with consequences in a game world. The queer video games scholar Bo Ruberg argues that game physics reflect the worlds that their developers and anticipated players have the capacity to imagine.2 For example, the gigantic, bouncing boobs and butts on femme characters like Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider franchise move in the ways that they do because their physics develops out of misogynist frameworks. Ruberg is interested in

imagining how a queer game physics divorced from normative understandings of motion and bodies would look, feel, and play out. A horse who never stops bucking, or can't be mounted, or even one who doesn't bother to put up any fight would wreck the taming challenge in a queer sort of way.

Motion capture data is hard to produce for large animals and game studios tend to buy this data from third-party libraries. Cetroid3D, a motion capture outfit based in the U.K., documented its process of creating an equine motion capture library, scanned on location at the Sparsholt Equine Centre in Hampshire. In the video the handler and horse are both wearing motion capture suits in an indoor practice ring with a soft, dirt floor.3 They perform many different maneuvers that might be useful in video games: rearing up, turning quickly to the left and right, trotting around. There is one maneuver shared by horse and rider whose utility to most games is less clear: the rider gently helping the horse to lay down.

The rider bends the horse's front left leg backwards at the knee, pulling the hoof sharply upwards towards the body by a tether. Simultaneously, she pulls the reins down toward the ground on the animal's left side. The horse drops to her left knee, while the handler continues to pull the horse's head sideways and downwards. The horse is resisting, not because she is afraid but because, for a horse, being forced to lie down is an unnatural maneuver toward vulnerability. Horses do choose to lie down in their day-to-day lives, to cool off or sleep, but they want to be in control of when,

how, and where this happens. This motion capture horse is well trained, she quits resisting and folds onto her left side, laying her head down in the practice ring dirt. The rider lays her hand firmly on the horse's shoulder, says something inaudible, perhaps in comfort, then walks away backwards, drawing her hand and then finger along the horse's flank as she retreats outside the frame, as if to say "stay down, you're okay." After a few moments, the handler returns and pats the horse on the shoulder, telling her with this gesture that she can get back up, then the handler jumps out of frame again.

It takes a great deal of training to get a horse to lie down on command, and the technique is controversial: some "horse whisperers" who specialize in taming the orneriest of mustangs, argue that this maneuver, when done safely, reduces aggression, because it forces the horse to embody a submissive pose. Others argue that forcing a horse to lie down is manipulative, dangerous, and

that forced submission is not a generative way of being in relation with animals. I don't know anything about horses so I can't weigh in, but I do know that in the thousands of hours I have spent riding horses in video games, I have never seen one lay down. I have only seen them die.

At £1,300, this lie-down gesture is by far the most expensive horse motion capture data in Centroid’s library (most gestures cost £200). Lying down is the closest approximation of playing dead that a real horse will perform for a camera, and horses need to die a lot in video games. The horse's work to rise back to her feet in the second half of the clip is useful for scenes in which a fall from heights, or an arrow to the side, is enough to knock a horse down, but not to kill her. The tender, slow exchange between horse and rider as the animal is eased gently towards the ground

in the motion capture could not be farther apart from the violence of killing horses in video games.

When the human figure guiding the horse to the ground is excised from the motion capture data, the horse simply crumples to the ground and dies. But the trust, and whispered words between horse and rider are still in there somewhere, shadows in the data that drives the action at some deeper level. These are traces of care to ponder in that meadow, wasting time watching my living game horse graze.

1 Jodi Byrd, “Indigenomicon,” Talk for SFU Digital Democracies Institute, 5 May 2021. Summarized here by Amy Harris: https://digitaldemocracies.org/jodi-byrd-indigenomicon/.

2 Bo Ruberg, “Queer Physics: The Gendered and Sexual Implications of How Video Games Move,” Talk at Society for Cinema and Media Studies Conference, 17 March 2021. Summarized here: https://twitter.com/SCMSQT/status/1372327149642915840.

3

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbNeRjfEPkw, see minute 2:10.

Cait McKinney is Assistant Professor in the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University. They are the author of Information Activism: A Queer History of Lesbian Media Technologies (Duke University Press, 2020), winner of the Gertrude Robinson Best Book Prize from the Canadian Communication Association, and a Lambda Literary Award Finalist for LGBTQ studies. They co-edited (with Allyson Mitchell) Inside Killjoy’s Kastle: Dykey Ghosts, Feminist Monsters, and Other Lesbian Hauntings (UBC Press and Art Gallery of York University, 2019), and a 2020 special issue of First Monday on HIV/AIDS and Digital Media.